Keynesian cogs

31 August 2024

I can’t pinpoint where I first read the phrase “cog in the machine”. It seems to be a popular idea on the internet, especially in the anti-capitalist discourse of the West. That is generic angst against the establishment. It’s a not-in-power younger generation going against the in-power older generation so I wouldn’t stress much meaning there.

But I, too, think about the phrase in various contexts. I am a fellow cog. I am an “office worker”. Most of my friends, engineers and MBAs, do work which is, well, not much engineering or business administration, but often feels like paper pushing as agents of a political class.

But I, too, think about the phrase in various contexts. I am a fellow cog. I am an “office worker”. Most of my friends, engineers and MBAs, do work which is, well, not much engineering or business administration, but often feels like paper pushing as agents of a political class.

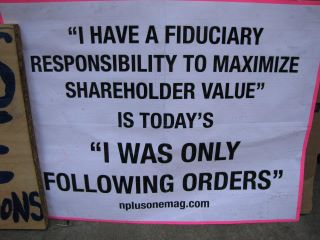

Let’s consider a mining company, which is an excellent example due to the raw necessity of its existence for the survival of modern civilisation. I wonder if layers of management exist just so that the customers are not directly slaving off the employees. The company seems to be a machine designed to abstract the economy’s needs enough that you cannot question the source.

Let’s consider a mining company, which is an excellent example due to the raw necessity of its existence for the survival of modern civilisation. I wonder if layers of management exist just so that the customers are not directly slaving off the employees. The company seems to be a machine designed to abstract the economy’s needs enough that you cannot question the source.

From another viewpoint, having work responsibilities is crucial to a meaningful life, lest we all drop into nihilism. It might not be the workload but the responsibility towards adding value to society in some form that drives the cogs. There is a sinister beehive/superorganism subtext that tries to explain the purpose of an individual life towards the progress of society.

If you choose to deny this program, you will find yourself a nihilist or, rather, a hedonist. I do not mean hedonism in an epicurean sense but as the literal interpretation of focussing on individual good. Such philosophies, in recent history, have led to an atrophy of society. And if you consider the declining fertility rates in advanced economies of the day, the atrophy is quite literal.

When I think of cogs, I think of Keynesian cogs. There is no such term before me, but that coinage sings to me. Read this famous essay by Keynes himself. Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren

Keynes had these arguments roughly 100 years ago that we would not need to work as much in future because rapid innovation brought forth by capitalism will reduce the need to.

I draw the conclusion that, assuming no important wars and no important increase in population, the economic problem may be solved, or be at least within sight of solution, within a hundred years. This means that the economic problem is not – if we look into the future – the permanent problem of the human race.

Keynes argues that in the future, we will work exclusively to satisfy a primal need to be useful, which he calls the “old Adam”.

For many ages to come the old Adam will be so strong in us that everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented. We shall do more things for ourselves than is usual with the rich to-day, only too glad to have small duties and tasks and routines. But beyond this, we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter – to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!

I would argue that Keynes’ has been correct in the aggregate that are better off than a century ago and need to put in fewer hours, but there are curious details. I found a critique which appears to argue on similar lines as the following. It is on my reading list and I would revise this article in the future if there are significant divergences.

The distribution of work responsibilities against socioeconomic class has fattened, but the tail on the lower end does not vanish. We all “office workers” doing paper pushing seem to be reaping the benefits. We live like nobles, satisfying the “old Adam” in us, but that is not true for the person who delivers your food from the app or the workers who clean our sewers.

True that there are machines to help them. Technology has improved safety for those workers over the years, but they are not Keynesian cogs, in any sense. They are doing their job both because society needs them to and because they need the money to survive. When nihilism knocks on their door, they answer with their aspirations that there’s a better future for them, their children, and their grandchildren.